We’ve spent an exciting day exploring the remote regions of Mexico’s Copper Canyon, and as sunset repaints the canyon walls, what better way to usher in the evening than with a cool refreshing margarita? Contreau or triple-sec, lime juice, ice, and, most important, tequila. But how much do we really know about this delightfully intoxicating beverage?

We’ve spent an exciting day exploring the remote regions of Mexico’s Copper Canyon, and as sunset repaints the canyon walls, what better way to usher in the evening than with a cool refreshing margarita? Contreau or triple-sec, lime juice, ice, and, most important, tequila. But how much do we really know about this delightfully intoxicating beverage?

Before the arrival of the Spaniards, fermented sap from the Maguey plant was extracted into a beverage known as ‘pulque.’ Pulque holds the esteem of being North America’s first distilled drink. Aside from that, origins of the liquor seem as ethereal as the effects it produces. Tequila branches from this phantom lineage by way of a small town with the same name in the state of Jalisco. In the ancient Nuahatl language, “tequila” translates to “place of the plant harvest” and represents the relationship between the region and the raw material—the Blue Agave.

There are over 130 species of agave. However, only one variety is used in the production of tequila according to standards set by the Mexican government. That variety is the Blue Agave, or Agave Tequilana Weber Azul. A common misconception is that tequila is made from a cactus. The Agave is actually closer in relation to succulents like the Lily or the Amaryllis even though it looks spiky in appearance. Only the hearts of the plant are used in distillation while the thick leaves are processed into fiber. Other varieties may be used in the formulation of tequila’s kindred spirit Mezcal, but only the Blue Agave is used to distill tequila. Mature agave at the time of harvest can grow 5 to 8 feet tall, span 7 to 12 feet across and, although not a cactus, can live up to 15 years!

Another myth infusing the agave spirits of tequila and mezcal turns over the worm. Drinkers and non-drinkers alike recognize the connection. However, like all things Tequila, origins of this curious practice of adding worms to bottles survives mostly as folklore, even though many believe it is more marketing strategy than authentic Mexican Tradition. In fact, only Mezcal carries the worm, this again due to the Mexican standards authority, Norma Oficial Mexicana (NOM). The worms are the thoroughly pickled larvae of the moth species Hypopta Agavis and, although not found in higher-priced bottles of Mezcal, are believed to enhance the flavor as well as act as an aphrodisiac. Viewed as a delicacy by many in Mexico, the Gusano Rojo (Red Worm) and the Gusano Blanco (White Worm) are safe to eat, even if their properties and histories are debatable.

Knowing tequila is not cactus and has no worm, it now comes down to the matter of taste. Tequilas divide into three groups agreed upon by aficionados in the industry. Like many beverages, Tequilas are classified according to their age. Blanco (white), also referred to as Plata (silver), is the youngest of the three types. Tequila Blanco is aged less than two months and is distinguished through its abrasive flavor. Also identified in this category is Tequila Oro (gold). This is a blend of the young Tequila Blanco and a more-aged variety, often mixed with coloring to resemble older vintages. Second of the three classes is Tequila Reposado (rested). This mid-aged tequila is known for its peppery aftertaste and has an age greater than two months but less than one year. The third and final variety is Tequila Anejo (aged). Tequila Anejo mellows for a period between one year and three years and finishes smoother on the palate as a result.

Aside from these distinctions, the sky (or the floor) is the limit. From the heart of the agave all the way to expensive, individually-numbered collectable keepsake bottles, the taste of tequila really boils down to the spirit of personal preference. Sipping, shooting, mixing or just plain drinking are all part of the charm bottled in this passionate product from Mexico. Curious connoisseurs searching for the flavor that suits best may even find themselves, suitcase in hand, bouncing across the border for a measure of Mezcal complete with worm. No matter how it’s served, the taste as well as the mystery surrounding this potent potable are sure to leave any traveler thirsting for more of Mexico.

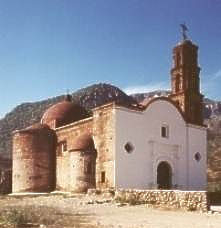

I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of

I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of

After a summer spent in the frigid waters of the Chukchi and Bering Seas, feasting on immense quantities of small crustaceans, the California Gray Whales begin their annual migration south to Mexico’s Baja California. Swimming 5000 miles along the North American coast, they arrive in the warm, protected bays to breed, give birth, and rear their infants.

After a summer spent in the frigid waters of the Chukchi and Bering Seas, feasting on immense quantities of small crustaceans, the California Gray Whales begin their annual migration south to Mexico’s Baja California. Swimming 5000 miles along the North American coast, they arrive in the warm, protected bays to breed, give birth, and rear their infants.

Easily accessible from La Paz and Loreto, Lopez Mateos and San Carlos are two coastal towns where pangas, small motor boats, depart for whale watching. Skimming along the water with frigate birds soaring overhead and whales breaching in every direction is an unforgettable experience.

Easily accessible from La Paz and Loreto, Lopez Mateos and San Carlos are two coastal towns where pangas, small motor boats, depart for whale watching. Skimming along the water with frigate birds soaring overhead and whales breaching in every direction is an unforgettable experience.

Who were these strangely-dressed people, who came from obscurity to outpace hundreds of experienced runners?

Who were these strangely-dressed people, who came from obscurity to outpace hundreds of experienced runners?