A whistle blows, and a conductor shouts the Spanish equivalent of “All aboard.” The diesel engines rev up, people relax in their seats, and off they go on one of the most famous and spectacular rail trips in the Western Hemisphere—the Copper Canyon train trip.

Officially called the Chihuahua al Pacifico Railroad, the rail line runs 406 miles from Los Mochis, on the Gulf of California, to the inland City of Chihuahua. Enroute, the train passes through the incredibly scenic area of rugged mountains and deep canyons in Northern Mexico’s Sierra Madre Occidental.

The rail line was first conceived in 1872 as the Kansas City Topolobampo Railroad by an American entrepreneur named Albert Kinsey Owen. By building a railroad from Kansas City across Mexico to the Pacific Coast, he could shorten the distance of the existing route by half, saving over 400 miles. Agricultural products from the interior of the United States could be transported over this shorter route to Topolobampo Bay, a natural seaport, and then carried on by ship to the Orient and western South America.

Construction of the railroad began in 1885. The project faced numerous difficulties, including lack of funds, poor management, some of the most rugged country in North America, the Mexican Revolution, and the building of the Panama Canal.

The rail line was finally completed in November of 1961, almost 90 years from its conception. The trains never did make it all the way to Kansas, but by this time improvements in U.S. domestic transportation had eliminated the need. It did, however, open up one of the most remote areas of Mexico and is still the only method of reliable transportation through the western Sierra Madres.

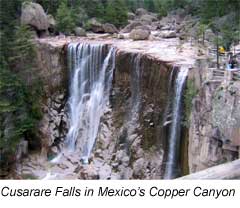

In order to complete the route, 86 tunnels and 37 bridges were constructed, totaling almost eleven miles of tunnels and 2¼ miles of bridges. The train climbs 8000 feet, plunges into a series of canyons and clings to sheer rock walls. At one point along the route it makes a 360 degree loop. At another point it enters a tunnel, makes a 180 degree turn, and exits the tunnel with the canyon now on the opposite side of the train. The views made possible by this masterful engineering feat, considered to be one of the most outstanding achievements of railway engineering in the world, are truly spectacular.

Pack your bags and join us on this remarkable journey. Along with experiencing this spectacular train ride, you will meet the people who make this area of Northern Mexico their home, including the cave-dwelling Tarahumara Indians, who have managed to preserve their traditional life-style despite the encroachment of Spain, Mexico, and the coming of the railroad.

To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

To begin to understand the Tarahumara ceremonies, one has to have a basic understanding of the Indians’ religion. The Tarahumara are outwardly Catholic, but their version of Catholicism is unlike any form we are familiar with.

Born in a rural Ohio farming community, Doug has followed many diverse paths. He was an army sergeant, a NASA electrical technician, an editor, a deputy sheriff, a bodyguard, and now an inn keeper. His greatest passion is horses—he owns at least a dozen, and he brags that they are the best trained and equipped in Northern Mexico.

Born in a rural Ohio farming community, Doug has followed many diverse paths. He was an army sergeant, a NASA electrical technician, an editor, a deputy sheriff, a bodyguard, and now an inn keeper. His greatest passion is horses—he owns at least a dozen, and he brags that they are the best trained and equipped in Northern Mexico. I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of

I arrive in Batopilas after an exhilarating drive down the winding dirt road from the mountain town of  Who were these strangely-dressed people, who came from obscurity to outpace hundreds of experienced runners?

Who were these strangely-dressed people, who came from obscurity to outpace hundreds of experienced runners?